St. Bernadette Soubirous & Our Lady of Lourdes

________________________

________________

The Song of Bernadette [ video ]

_________________

Saint Bernadette Soubirous (1844-1879)

I. Childhood - Setting the scene up to the first of 18 apparitions of the Blessed Virgin Mary to Bernadette.

Saint Bernadette Soubirous, was born on the 7th January, 1844 in Lourdes, population of about 4000, and not far from Tarbes, in southern France close to the Spanish border, and baptized two days later, her baptismal name being Marie Bernarde; in Lourdes she was always known by the graceful diminutive, Bernadette.

This is the story of a 14 year old peasant girl raised in dire poverty and unable to read, to whom Our Lady appeared eighteen times to Bernadette, and who later became a nun in the convent of Nevers, where she reached such holiness that God saw fit to preserve her body incorrupt to this day.

Bernadette's father, Francois Soubirious was a miller and at the time of Bernadette's birth he was twice the age of his wife, Louise. Both were outstanding and devout Catholics in which Mass and daily recitation of the Rosary of the Blessed Virgin, morning and night prayers were part of their daily lives.

|

Bernadette's parents- Francois and Louise Soubirous |

Early Home Life In The Mill

The house Bernadette was born in was a mill called the Boly, named after an English doctor who owned it in the seventeenth century, and was located along with six other mills to the north of Lourdes along the banks of a tributary of the Gave River.

|

Bernadette's birth place - the Boly mill |

It was not a large one, and before Bernadette's father, Francois Soubirous married, he helped out at the Latour mill which was leased by his parents, Joseph and Marie Soubirous.

He became engaged to Louise Casterot the daughter of the Casterots who owned the Boly mill, and eventually the married couple took over the Boly mill and paid rent to Louise's mother, after madam Casterot's husband died.

Bernadette's parents, Francoise and Louise Soubirous were married in 1843, and nine children were born of their marriage, five of whom died in their childhood. Bernadette being the eldest, was a strong healthy child up until the age of six, but unfortunately suffered from asthma which was to trouble her for the rest of her life.

She was, nevertheless, a lovable child with a sweet smile, but her growth was somewhat retarded, and choking fits frequently pulled her up in the midst of her games.

In spite of all this, she was already making herself useful in the house taking care of her little sister, Toinette who was two and a half years younger than herself.

|

Marie Antoinette "Toinette" Soubirous |

The departure of Grandmother Casterot from the mill, who had been living with them and helping run the mill, being experienced in handling the affairs of the mill, keeping accounts and mill bookings for the patrons, was sorely missed by both Francois and Louise Soubirous who both could not read or write.

The demise of the mill was partly the blame of the generosity of both Francois and Louise, who often used to cancel certain debts out of charity, and besides, they were soon unable to afford to replace worn-out sifters for the mill.

In 1854, when Bernadette was ten and a half years old, the owner of the Boly mill (Abadie-Boly, to whom the Casterots were paying a rental for the use of the Boly mill) decided to get rid of the mill.

Madame Casterot decided to rent in her name, the Laborde- Louisel mill to house and provide for the whole family. The mill had a very small output and had to compete against the larger neighboring mills, and Francois had to take on odd jobs to make ends meet.

The winter of 1854 on the feast of Friday 8 December passed completely unnoticed by the poor Soubirous. There was no time to think about the celebrations taking place in Rome where Pope Pius IX pronounced ' the Virgin Mary was preserved from the stain of original sin from the moment of her conception.'

|

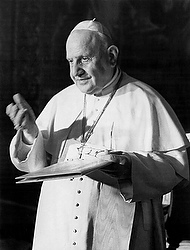

Pope Pius IX |

At the Laborde mill, it was a struggle to provide for their daily bread, and another mouth had to be fed after Justin Soubirous was born on February 28, 1855.

Bernadette had just turned eleven.

In watching her own dear family suffer and in her own sufferings, Bernadette matured early, becoming detached from the world. Small in build and racked by asthma, she took on tasks seemingly beyond her strength. One can picture her holding in her arms the baby Justin. The other two, Jean-Marie and Toinette were a little wild, but the eldest sister knew how to scold them on occasions and make them obey her.

Louise Soubirous could take on work without anxiety for under Bernadette's care there would be no trouble at home.

The following delightful incident shows how Bernadette at such a tender age was as downright as she was sensible.

One day in July 1855, the mother had arranged with a cousin, Catherine Soubirous, and another Lourdes woman, to go and help out with the harvest in a field on the Mengalettes' farm.

Between nine and ten in the morning, Bernadette appeared on the doorstep with her baby brother in her arms. Romaine, the farmer's daughter was there and welcomed her. She was to remember this humble meeting all her life; she even noted that Bernadette, whose 'face was round and pretty, with lovely, very gentle eyes', had her usual kerchief on her head, a shawl over her shoulders, her bare feet in sabots, and her dress reaching down to the ground. She seemed tired, 'and there was every reason'.

'In she comes then,' relates Romaine Mengelatte, 'and very simply, very nicely, she says to us, "Would you kindly tell me where your field is? I must carry my little brother to my mother, for he wants to be suckled." '

A neighbor, who was also off to join the harvesters, took Bernadette at once to the Mengelattes' field.

On October 23, 1855 Louise's mother Claire Casterol passed away. Her experience was sorely missed by the Soubirous in the affairs of the mill.

From the division of the property Bernadette's parents strove to earn their daily bread rather than beg.

Francis rented a hut 3 miles east of Lourdes in Arcizac, and took charge of a mill near by. Louise took on jobs on the land when required.

The Sisters of Charity of Nevers had come to Lourdes in 1834, not far from Bernadette's home, and ran a school, however Bernadette seldom went to school as her duties of nursemaid did not allow her to go often, so she was unable to read.

Her only prayer book at Mass was a small rosary.

At home she was she was no trouble to anyone. I always found her good tempered and docile; when she was scolded she never answered back, her Aunt Bernarde was to later affirm.

In the course of 1856, the Soubirous were now at the end of their resources and had to leave Arcizac, where their next home was a wretched hovel room sublet to them in the Rue du Bough.

Bernadette was now twelve, and helped, together with Toinette, to keep the fire going and warm up the soup for the family.

This was an age of scant help for the poor.

From The Mill To The Dungeon

In 1856 around All Saint's Day, they would be seen loading a handcart with what remained of their furniture and crockery, their destination being the old prison or cachot. This prison was owned by Andre Sajous, a cousin of Louise who lived in it.

|

The cachot or dungeon where the Soubirous family were living at the time of the apparitions |

Francois begged him to let the old dungeon to him. It comprised two floors, the first floor had two rooms occupied by Andre Sajous, while the ground floor was used as a workshop.

Jeanne Vedere spent a night there in 1858 and found they had 'absolutely nothing but some necessary bits of furniture and linen; 'there was a cupboard, a trunk, some chairs and three beds - one for the parents, one for the two girls and one for the two small boys.' - that left precious little space in this small home measuring four yards by five yards.

Francois continued to do odd jobs, while Louise went to the forest and did washing or charring in the town. Toinette had turn ten and attended the Sister' school fairly regularly.

Bernadette was repeatedly heard to say that books were not meant for her. She was now thirteen and the Sisters did not know quite know which class to put her; the most she managed was to scrawl rather badly, two or three letters on a slate..

Then there was the asthma, but above all she was needed at home.

Her little sister, Toinette, nearly eleven, could read, had better health and could easily have been taken for the eldest in the family, and also there was talk of her First Communion. Bernadette would have loved to go to catechism classes!

'Have patience, your turn will come,' her mother promised.

At night she would when her asthma prevented her from sleeping, she used to cry over the heart-breaking poverty of the home, over her ignorance and her frustrated longings. When morning came, once she had said her prayers, she regained her child-like gaiety. She would wash and dress her little brothers and join in their games.

'Never,' testified Andre Sajous, 'would you have heard them complain that they were hungry. But how often have I seen Bernadette, Jean-Marie and little Justin laugh and skip on an empty stomach!'

Bernadette - Shepherdess In The Hills Of Bartres

|

The Hills of Bartres where Bernadette was a shepherdess |

Towards the end of June 1857, Bernadette's mother Louise decided it would be easier for Bernadette to attend school and catechism at Bartres, (roughly 3 km north of Lourdes), rather than Lourdes, and so the Lagues' servant, Jeanne - Marie Garros, came to Lourdes to fetch her, commenting, 'she hadn't much to pack,' said Jeanne-Marie, and more than once during her stay at Bartres, I lent her some of my linen while she washed her own.'

The Lagues had kept up their friendship with the Soubirous despite their poverty, and the foster-mother readily agreed to take Bernadette in as an extra servant without wages, of course, just out of friendship.

Bernadette was to look after the five little Lagues children, outside of school hours and Catechism, which attended regularly for some weeks, however, M. Lagues, being a practical man, noting that the servant, Jeanne-Marie did all the work of the house, decided, since Bernadette had little else to do, but take care of his children, she could take care of the lambs, for the Lagues owned a large flock of sheep, some cows and large scattered tracts of land.

'But what about school and Catechism?' protested Bernadette timidly.

'Don't worry at all,' the man replied; 'your foster-mother will arrange all that in good time.'

So now Bernadette became a shepherdess.

|

Bernadette-The Shepherdess |

Up early in he morning she helped the mother to wash and dress the children, did the housework with Jeanne-Marie, and then made her way to the stable, accompanied by Pigou, one of the farm dogs, and together with the lambs they would go to the rolling hills. In a basket on her arm the little shepherd-girl carried her knitting, a garment to mend and provisions for the whole day.

Bernadette divided her time between work, play and saying her rosary on her cheap twopenny rosary which her mother had given her.

Her pleasures were as simple as her soul.

How silent it was on the slopes of this valley almost the whole day through. She would gaze beyond Lourdes, which she could no longer see, to the Pyrenees mountains, which she could view from the top of the valley, their peaks dusted with snow ... God made all that she said to herself, the God she understood was the Creator, and also the One who remained hidden in the Tabernacle of the church.

|

Hills of Bartres where Bernadette was a shepherdess |

While she was saying her rosary her thoughts would also fly to the 'dungeon' in Lourdes, where her loved ones were down there in that gloomy hovel.

Francois Soubirous often took the time to visit his daughter as often as he could, and she welcomed him, with a cry of delight.

M. Lagues seldom sent Bernadette to school, and then only when he had to, as M. Lagues said, 'she looked after the sheep very well', which seemed to him to be a very good reason not to do so.

Towards the end of her life, Bernadette was asked if she went to school at Bartres. She replied, 'I scarcely ever went to the school, and when I did, I learnt nothing.' She also admitted she went only rarely to Catechism.

Shortly before Christmas 1857, Bernadette became homesick and wished to return to her family in Lourdes so that she could join a class and prepare for her First Communion.

Around the 28th of January, 1858, Bernadette returned home to Lourdes. She had just turned fourteen. She still looked no more than 'ten or eleven' - she had remained so small.

After embracing her family, Bernadette cried out joyfully: 'Now at last I shall be able to go to school and Catechism! That's why I have come back!'

The return of Bernadette to her family put an extra burden on their poverty, but they owed it to this much neglected child.

The next day Bernadette appeared at the Hospice school and the Sisters immediately enrolled her among the future First Communion class who were following the Catechism lessons given in the Hospice by the chaplain, Abbe Bertrand - Marie Pomian, the senoir curate to the parish priest, M Peyramale.

After the wide-open country and sunshine of the Bartres hill sides, to Bernadette at this point in time, they were not so dear to her as the narrow Rue-des-Petits-Fosses, the stuffy atmosphere and black-grimed beams of the dungeon.

But in this wall of gloom there would soon be a portal of light, for heaven had resolved to reveal itself once again on the soils of France.

'At fourteen, not knowing how to read or write, and a complete stranger to the French language and ignorant of the Catechism, Bernadette looked on herself as the most worthless child of her years.'

At the appointed hour a voice of exceeding sweetness confirmed the eternal choice. 'This one!'

__________________

II. The Apparitions Begin - First Apparition. Thursday 11th February, 1858.

Thursday, February 11th, 1858 dawned over Lourdes like other winter days; a veil of mist shrouded the town and the surrounding mountains.

The air was cold and damp; it was holiday time for the school-children, and Francois was tired and remained in bed that morning, however as soon as there was enough daylight the young Soubirous children were up and running about in that gloomy room.

Before 11 o'clock that morning, the mother was making ready to go out to gather firewood. Just as she was ready to leave, Jeanne Abadie, a class mate of Toinette, met her at the doorway and asked her where she was going. 'Where are you going to, Louise?' 'To the wood, ' the mother replied?

'We'll all go,' said Jeanne decisively, starring at both Bernadette and Toinette. 'Oh, yes!' they shouted, we'll all go. can't we Mamma?' Bernadette had a slight cold, and her mother objected saying it was too cold and damp for her.

'But, Mamma', Bernadette, the former shepherdess remarked, 'this sort of weather never stopped me going out at Bartres.'

'Very well, then!' Off you go with Jeanne and Toinette, but you must take the cape.'

At the dungeon they always spoke of the cape as there was only one, not a new one, but an old white one, much patched, having been bought at a second hand store opposite the church. Bernadette had washed it several times.

They wore sabots without stockings, but on account of her asthma, her mother made her wear stockings.

As they made their way a neighbor spotted the girls that morning and asked where they were going. They replied ,to get firewood.' The woman advised them to go M. de Laffitte's meadow, where the owner had been recently felling trees.

This meadow was reached by a foot bridge, enclosed on one side by the River Gave and the other side by a canal whose current worked the Savy flour mill.

A little below the mill, the Merlasse streamlet flowed into this canal, which eventually rejoined the stream by the base of the rocky promontory, called the Massabielle.

It was the first time Bernadette had ever entered these parts.

On this 11th day of February , 1858, the mill was idle, being under repair, and there was practically no flow of water.

The space left in front of the grotto was at low water was about five yards. At the entrance lay some scattered boulders. To the right of the cave, some three yards above the narrow bank, there was an oval recess.

From this cavity, the stems of several shrubs and the large branches of an eglantine forced their way out; they hung down very low along the rock.

In spring the wild rose bush was ablaze with white blossoms!

Jeanne Abadie relates that the water was knee deep, and was exceptionally low that day. To reach the grotto they had to wade across and the ice cold water brought tears to both Toinette and Jeanne's eyes.

Bernadettes dared not follow, obeying her mother's instructions, yet she needed to cross over to join up with Toinette and Jeanne, who by now were heading off to collect their faggots of firewood before Jeanne had called out to Bernadette to stay where she was.

Bernadette was now all alone.

Leaning against a boulder, a little to the right of the large cave, Bernadette had finally decided to take off her stockings in order to cross the stream to catch up with Toinette and Jeanne.

Now was to begin the series of wonders for which the unwittingly predestined child had come, a place she had no idea of going to, but where she was expected.

Bernadette's account of what followed:

I had hardly begun to take off my stocking when I heard the sound of wind, as in a storm. I turned towards the meadow and I saw the trees were not moving at all. I had half noticed, but without paying any particular heed, that the branches and bramble were waing besides the grotto.

I went on taking my stockings off, and was putting one foot into the water, when I heard the same sound in front of me. I looked up and saw a cluster of branches and brambles underneath the topmost opening in the grotto tossing and swaying to and fro, though nothing else stirred all around.

Behind these branches and within the opening, I saw immediately a girl in white, no bigger than myself, who greeted me with a slight bow of the head, at the same time, she stretched out her arms slightly away from her body, opening her hands, as in pictures of Our Lady; over her right arm hung a rosary.

I was afraid. I stepped back. I wanted to call the two little girls; I hadn't the courage to do so. I rubbed my eyes again and again: I thought I must be mistaken.

Raising my eyes again, I saw the girl smiling at me most graciously and seeming to invite me to come nearer. But I was still afraid. It was not however a fear such as I have had at other times, for I would have stayed there for ever looking at her: whereas , when you are afraid, you run away quickly.

Then I thought of saying my prayers. I put my hand in my pocket. I took out the rosary I usually carry on me. I knelt down and tried to make the sign of the Cross, but I could not lift my hand to my forehead: it fell back.

The girl meanwhile stepped to one side and turned towards me. This time she was holding the large beads in her hand. She crossed herself as though to pray. My hand was trembling. I tried again to make the sign of the Cross, and this time I could. After that I was not afraid.

I said my Rosary. The young girl slipped the beads of hers through her fingers, but she was not moving her lips.

While I was saying the Rosary, I was watching as hard as I could. She was wearing a white dress reaching down to her feet, of which only the toes appeared. The dress was gathered very high at the neck by a hem from which hung a white cord. A white veil covered her head and came down over her shoulders and arms almost to the bottom of her dress. On each foot I saw a yellow rose. The sash of the dress was blue, and hung down below her knees. The chain of the rosary was yellow; the beads white, big and widely spaced.

The girl was alive, very young and surrounded with light.

When I finished my Rosary, she bowed to me smilingly. She retired within the niche and disappeared all of a sudden.

When questioned later, Bernadette was to give further details about the 'young girl' who had appeared:

A 'golden cloud' preceded her, she said, then the halo: the latter remained for an instant after she had disappeared. She herself was as if penetrated with a 'soft light', which neither hurt or dazzled the eyes.

Her face was oval in shape, and 'of an incomparable grace', her eyes were blue, her voice 'Oh, so sweet!' Her hair scarcely showed through the veil on her forehead, and was clearly visible only at the temples.

Her bare feet rested, at the threshold of the niche, on a carpet of grass and twigs, which the child sometimes called moss. Her hands, when she kept them joined, were pressed together along their whole length, palm to palm. Her rosary, with its white beads widely spaced, was not, strictly speaking, a 'rosary': it had only five decades, the same as Bernadette's; the Vision and the visionary kept time with each other as they slipped the beads through their fingers. While they were doing so, the 'girl' of the grotto, at her first Apparition, did not move her lips except to smile; yet Bernadette would have occasion later to explain that although during the recitation of the Pater and Ave she seemed to listen without moving her lips, when they came to the Gloria Patri she bowed her head and visibly recited it.

This last detail, which the little one in her ignorance could not have invented, reveals an accurate and deep theological truth. the Gloria, which is a hymn of praise to the Adorable Trinity, and is Heaven's Canticle, is indeed the only part of the Rosary suitable for Her, whose name Bernadette would not learn for another month. The Pater is the prayer of needy mortals, tempted and sinful, on their journey to the Fatherland; as for the Ave, the Angel's greeting, this could be used only by the visionary, as the Apparition had no need to greet her own self.

The vision had lasted the space of a Rosary, said without distractions and without hurry.

Toinette and Jeanne, having finished collecting their wood, caught a glimpse of Bernadette towards the end of her ecstasy, as they were making their way back from the banks of the Gave towards the grotto, and noticed that she was 'still on her knees, looking towards the niche', according to Toinette's evidence.

I called out to her: 'Bernadette!' three separate times. She made no reply and did not turn her head.

On nearing the grotto, I twice threw a small stone at her and hit her once on the shoulder; she did not stir. She was white, as though she was dead. I was afraid. But Jeanne said to me: 'If she were dead, she would be lying down'. I wanted to cross over ...

All of a sudden, Bernadette became herself once more, and looked at us. I said to her; 'What are you doing there?' - 'Nothing.' - 'How stupid of you to pray there!' - 'Prayers are good everywhere.' Then she crossed modestly over the canal.

Bernadette confided later to her cousin, Jeanne Vedere: 'I was astonished on entering the canal to find the water warm rather than cold.'

Bernadette[continued Toinette] put on her stockings, stirring on a rock, and did not seem to be cold ... then she said to us, 'Did you see anything? '-' No. And you, what did you see?' - 'Nothing then.'

Jeanne Abadie, in a hurry to back home, went ahead of her companions, the basket of bones on her arm, and a bundle of wood on her head. Bernadette and her young sister divided their share of the wood into two other faggots.

|

The Lady appears to Bernadette for the first time |

[to be continued ...]

Photo of Bernadette when she was between 16 and 18 years old |

Bernadette Soubirous in the grotto of Lourdes, October 1863. |